There have been a lot of ideas bouncing around since starting this project, a few of them are briefly discussed below and will hopefully be elaborated upon in the near future. These points are mostly based upon the idea of air and how it has been imagined since antiquity.

The desire to work with airs apart from their sonorous renderings in the ear (which describes the state of vibrational matters I normally choose to work with) was driven by an interest in thinking about sound beyond the ear, the nature of sounds not heard. Removed from what is normally thought as their constitutive organ (according to which a movement of the air is only called sound insofar as someone hears it) these inaudible ‘sonorities’, or more simply vibrations, are constituted purely according to that which resists of exceeds the possibility of perception, existing as that which sound is in-itself when there is no one around to hear it. This has taken me to the elements making up these disturbed bodies of air that are named sound upon setting the ear in motion, the minuscule elements that make up the medium through which we most commonly hear. The work I’m undertaking as part of Invisible Cartographies is a set of preliminary experiments in engaging with some of the constituent elements of the airs through which we hear that persist beyond acts of audition, something which has lead towards basic experiments with mapping the components of atmospheric chemistry. The processes described by chemistry draw attention towards a weirdly vitalistic creativity, foregrounding the interactions, interrelations and contingencies of diverse bodies, distinct if a little fuzzy round the edges. The vitality ascribed to airs or gaseous bodies is highlighted by the historian Alain Corbin in his fabulous book The Foul and The Fragrant when he states that, during the late eighteenth century, “to study airs was study the mechanisms of life” (16). Air, while linked to life forces through the vitalistic assertion of an equilibrium between airs and organisms (human, animal, plant … ) is also described by Corbin as “the laboratory of decompositions”, therefore linking it to a process more readily linked to decay and death through the dissolution of bodies into the realm of the imperceptible. Airs have been variously thought to account for both the constitution and dissolution of bodies throughout history, and so this “laboratory of decompositions” attests to a two way motion as the decomposition of one body feeds into the composition of another, establishing a dynamic equilibrium between bodies, whether these be bodies of water, air or animal bodies. Composition is then thought as an ambiguous process enfolding decomposition within its operations, operations that are negative from the perspective of the integrity of the individual undergoing decay, yet positive from the perspective of the infinite interactions that each constituent element or particle enters into within the complex interactions of airborne compositions. Accounting for its contingencies and interactions, a body of air is perhaps best thought of as a particular continuum, being comprised of elementary particles that are shared or passed between individuals in varying degrees of composition and decomposition.

In addition to this weird vitalism that thinks of air as an interactive field of (de)compositions, I’d like to highlight a more fundamental theory of airs that extends back in time around 2500 years, that serves as a link between airs and the constitutive movements of sound, a theory that states that the movements comprising sounds also comprise rocks and earth.

Apart from chemical and particular interactions, there is a productivity to the contractions and rarefactions of the air which allows for its rendering as sound in the ear or as a touch on the skin. The contractions and rarefactions or disturbances of the air productive of what we might call sound objects or audible events were, for Anaximenes (585 - 528 BC), the same disturbances or vibrations that produced stones and earth. Anaximenes’s position on the creative contractions of air is summarised by Theophrastus (371 - 287 BC):

Anaximenes, son of Eurystratus, of Miletus, was an associate of Anaximander who says, like him, that the underlying nature is single and boundless, but not indeterminate as he says, calling it air. It differs in essence in accordance with its rarity or density. When it is thinned it becomes fire, while when it is condensed it becomes wind, then cloud, when still more condensed it becomes water, then earth, then stones. Everything else comes from these. And he too makes motion everlasting, as a result of which change occurs.

I keep this last line in the quote as it is often the movements of diffuse spatialities or airborne bodies that bring about the vitality ascribed to them, as sound or fresh air are often described as bringing a space “to life” by virtue of the movement they instil in what is otherwise perceived to be static, dormant or dead.

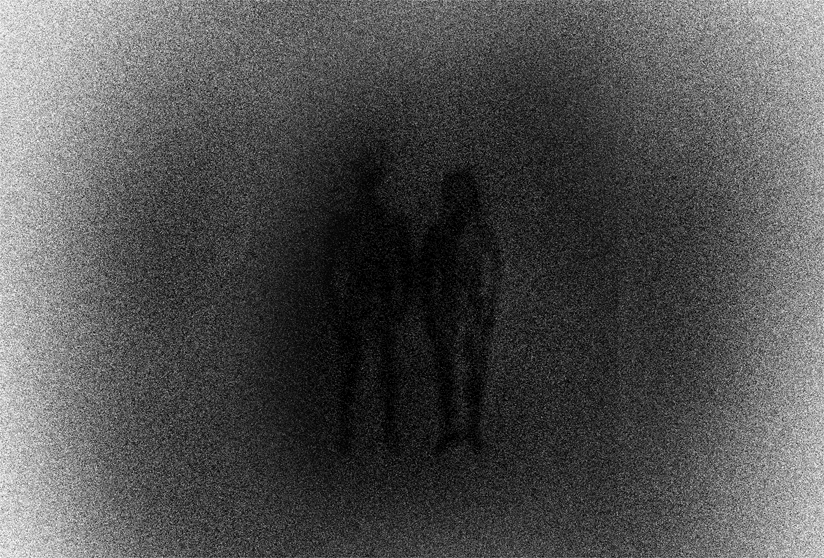

The above diagram was drawn up to express units of existence, whether rocks, trees or humans, as contractions of a kind of mist or cloud of particles, a confused material substrate from which identifiable forms emerge. It is in this sense that I find a link between these thoughts on air and the noises I normally work with: air and noise find a certain relation in that both constitute a background to existence, comprising that which slips most easily into imperceptibility through fluctuations in sensory thresholds, while remaining the particular objects of a subliminal influence. The confused bodies of air and noise constitute backgrounds which through their contractions produce the figures appearing to the fore.