In carrying out research into the history of air while working on this residency, Ruskin came up a number of times, which is not surprising giving the location of the residency. I know very little of Ruskin, but have found his meteorological speculations fascinating since digging out his two lectures on The Storm Cloud of The Nineteenth Century. Ruskin made many studies of clouds, some of which I had the pleasure of seeing last Friday at Brantwood. Rather than his aesthetics, it is on the concepts presented in his lectures on clouds, presented to the London Institution in 1884, that I’d like to focus on now. All the quotes below are taken from the transcript of the lectures available here: http://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/20204 . What follows is a few quick notes on what I consider the highlights of these lectures. It is these lectures that I’m particularly interested in as they contain a mixture of careful description with physical and mystical speculation on the nature of diverse clouds. Perhaps unsurprisingly, clouds are defined as such by Ruskin according to their visibility, yet this distinction is not made without ambiguity as Ruskin will speak of airborne bodies composed of “an invisible, yet quite substantial, vapour; but not, according to our definition, a cloud, for a cloud is vapour visible.” While not a cloud, these invisible vapourous bodies nonetheless remain substantial, affective objects. Ruskin goes someway to beginning a taxonomy of clouds based around floating “sky clouds” and falling “earth clouds”, but it is the bodies of air that are not quite clouds that I find particularly interesting, the mists that Ruskin identifies as existing in-between sky and earth clouds. It is the status of being in-between that is particularly interesting as it is that which does not quite satisfy Ruskin’s taxonomic criteria for cloud status that pertains to the invisible and to the diffuse bodies of a subtle and subliminal influence. This in-between status alludes to a body of air in transformation, between states, in flux; it is this being in-between or interstitial existence that is in part behind Deleuze and Guattari’s mention of fog and mist where they relate both theses states of the air to what they call a haecceity, a being that is in the process of becoming something else, always in a state of change, ephemeral and contingent: ‘ a haecceity is inseparable from the fog and mist that depend on a molecular zone, a corpuscular space’, (A Thousand Plateaus, 301).

Beyond Ruskin’s general work on clouds, it is the concern he expressed for a dark and menacing wind or cloud particular to the 19th century that is really interesting: “This wind is the plague-wind of the eighth decade of years in the nineteenth century; a period which will assuredly be recognized in future meteorological history as one of phenomena hitherto unrecorded in the courses of nature, and characterized pre-eminently by the almost ceaseless action of this calamitous wind.” This calamitous wind is most easily characterised as the product of rapid industrialisation and signals Ruskin’s environmental concerns, but what is of particular interest is that the action of the plague-wind or cloud cannot be neatly restrained to the problem of pollution, insofar as Ruskin bears what we would now refer to as a broadly ecological understanding of its contingencies, interconnections and extensions, with cloud formations occupying the position of a medium between industry, politics morality and subjectivity. The extent of Ruskin’s implication of the plague-cloud within an ecological field comprising the political, spiritual and environmental can be seen in the second of his lectures on the subject where he describes “the clouds and darkness of a furious storm, issuing from the mouths of fiends—uprooting the trees, and throwing down the rocks, above the broken tables of the Law, of which the fragments lie in the foreground.” Here the nephological is understood to seep not only into organic bodies but to infiltrate the Law, which due to its capitalisation should be read as referring to the domain of morals and ethics in general, to an order of social power and control.

Ruskin’s plague cloud “looks partly as if it were made of poisonous smoke; very possibly it may be: there are at least two hundred furnace chimneys in a square of two miles on every side of me. But mere smoke would not blow to and fro in that wild way. It looks more to me as if it were made of dead men’s souls—such of them as are not gone yet where they have to go, and may be flitting hither and thither, doubting, themselves, of the fittest place for them.” Here the plague-cloud is not limited to being thought as solely produced by furnaces and composed of the diffuse elements of burnt offerings to industrial progress (the “sulphurous chimney-pot vomit of blackguardly cloud”), but as being confused with the soul and the flight of the dead, echoing conceptions of the air as the medium of the spirits that has persisted for millennia. The broadly ecological (by which I mean an understanding of the interconnectedness of all things rather than the strictly ‘natural’) implication of the nephological, of clouds, mists and winds, within a distinctly moral and spiritual order can be found in Ruskin’s conclusion to the first lecture:

“Blanched Sun,—blighted grass,—blinded man.—If, in conclusion, you ask me for any conceivable cause or meaning of these things—I can tell you none, according to your modern beliefs; but I can tell you what meaning it would have borne to the men of old time. Remember, for the last twenty years, England, and all foreign nations, either tempting her, or following her, have blasphemed the name of God deliberately and openly; and have done iniquity by proclamation, every man doing as much injustice to his brother as it is in his power to do. Of states in such moral gloom every seer of old predicted the physical gloom, saying, “The light shall be darkened in the heavens thereof, and the stars shall withdraw their shining.” All Greek, all Christian, all Jewish prophecy insists on the same truth through a thousand myths; but of all the chief, to former thought, was the fable of the Jewish warrior and prophet, for whom the sun hasted not to go down, with which I leave you to compare at leisure the physical result of your own wars and prophecies, as declared by your own elect journal not fourteen days ago,—that the Empire of England, on which formerly the sun never set, has become one on which he never rises.”

The plague-cloud here constitutes a grim and filthy prophecy, being enfolded within a moral, spiritual and political order. That these clouds should have been thought by Ruskin to have moral and spiritual implications is not entirely surprising when taken in the context of certain aspects of scientific and philosophical thought prevalent around the time he presented these lectures. During the 1870′s, there are accounts of not only the physical impacts of diverse atmospheres such as tropical climates upon immigrant and primarily colonial populations, but also the moral impact of the climate upon its ill-prepared, ill-tempered, or ill-weathered European subjects who sought to exploit the resources of far-off lands ( a nice introduction to these ideas can be heard here http://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/b00wfhgg ). While there is a highly dangerous element to this kind of thinking on climates and atmospheres, a danger that persists where environmental determinism is allowed to remain unilateral, according to which people are simply a product of their environment and the subjects of climate, where the influence of atmospheres and environments is taken amidst a broader approach to atmospheric influence and environmental interactions it helps account for the nuances of ecological relations, including (as in Ruskin’s work) the natural, synthetic, political and spiritual.

There are a few fragments within the two lectures that I find particularly interesting from the point of view of artistic practice and spatial productions, namely the moments where Ruskin considers the composition of clouds that are not normally considered natural or strictly meteorological. Considering the malignant qualities of plague-clouds, Ruskin briefly wonders whether “perhaps, with forethought, and fine laboratory science, one might make it of something else”. Here I’m inclined to speculate on Ruskin’s spirit of invention, imagining it turned towards the production of clouds as an artform or architecture of the air, and imagine Ruskin dabbling in the production of clouds of a more agreeable composition, releasing them from a laboratory that was never built onto the side of Brantwood. We can find a further fragment of a larval nephological synthesis in Ruskin’s question: “What—it would be useful to know, is the actual bulk of an atom of orange perfume?—what of one of vaporized tobacco, or gunpowder?—and where do these artificial vapors fall back in beneficent rain? or through what areas of atmosphere exist, as invisible, though perhaps not innocuous, cloud?” In these questions we find Ruskin considering atmospheric production by means of perfume, explosions and smoking, and an altogether more experimental mode of thinking on the subject of atmospherics and cloud production.

Hopefully by the end of this residency I can draw up a reading list to enable me to take these speculations further.

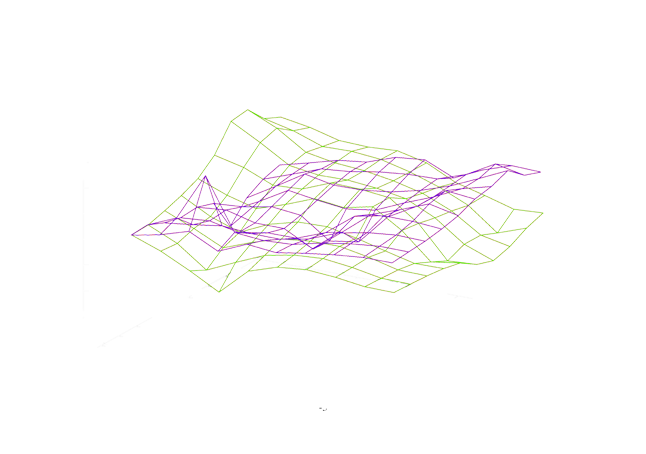

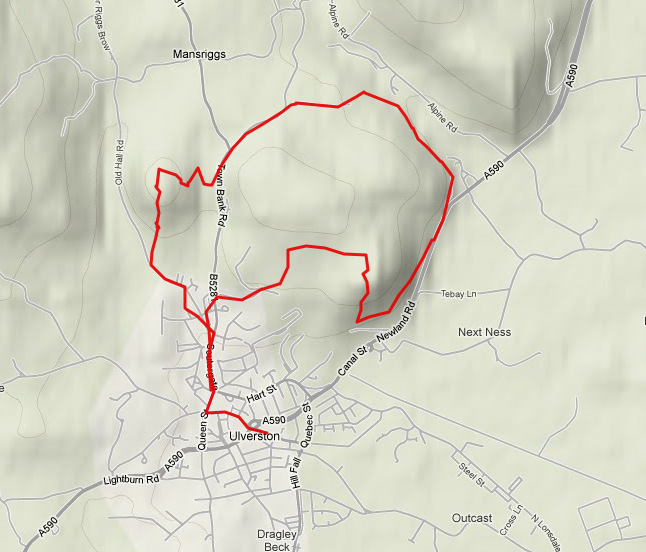

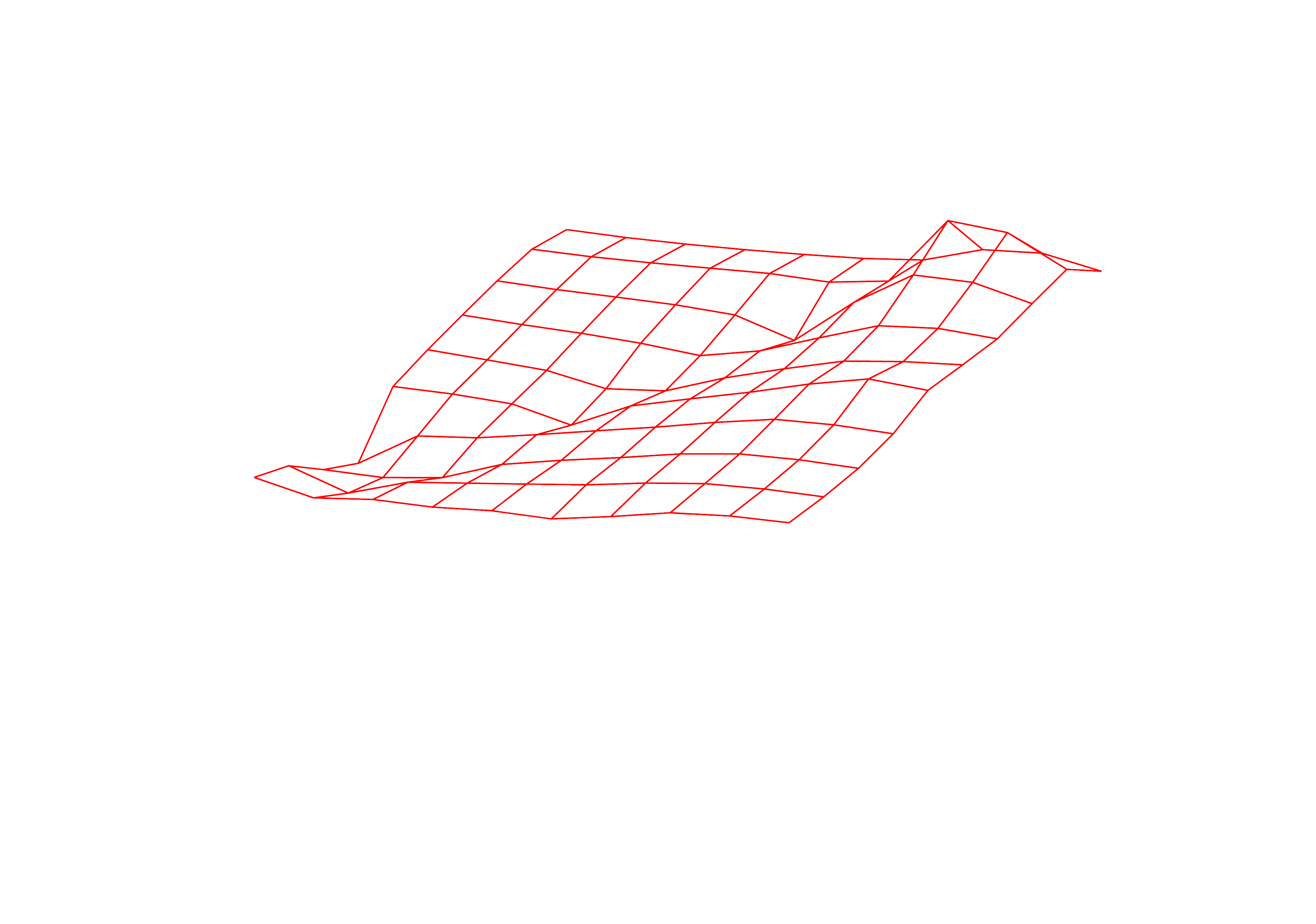

These final images were taken during an earlier trip to Coniston to gather samples in Ruskin’s garden: